December 2005

THE OTHER MOVEMENT THAT

ROSA PARKS INSPIRED

by Charles Wilson

By Sitting Down, She Made Room for the Disabled

October 30, 2005 - Washington Post - On an unseasonably warm September day in 1984, about a dozen men and women rolled their wheelchairs in front of a city bus that was pulling onto State Street in Chicago. Then they sat there and didn't move. The group had no secret agenda; they simply wanted to make a point. Days before, the Chicago Transit Authority had announced that it was purchasing 363 new public buses -- and that none of them would be equipped with wheelchair lifts to serve disabled passengers because the lifts had been deemed too expensive. This ragtag group of wheelchair riders, who were affiliated with a disability rights organization called ADAPT, or Americans Disabled for Accessible Public Transit, decided to protest that decision by obstructing a bus until the police carted them away. Every one of them wore a simple paper name tag, the sort that you would normally see at a meet-and-greet. They all said: "My name is Rosa Parks."

|

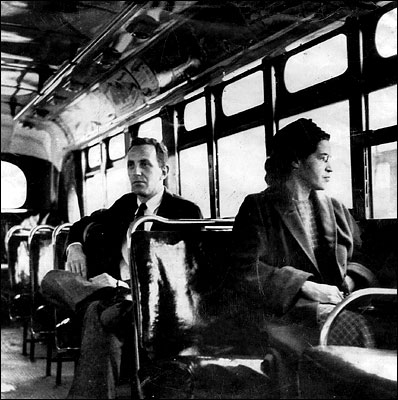

| Rosa Parks Photo by Montgomery Advertiser |

Rosa Parks' act of courage in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955 did more than dismantle the system of racial segregation on public transportation. Her refusal to give up her seat to a white man also created a legacy she never could have foreseen. It was through Parks' example that the disabled community transformed its own often disorganized cause into a unified disability rights movement. "Had it not been for Parks and the bus boycott, there is no question that the disability rights movement would have been light-years behind, if it would have ever occurred,"

says Michael Auberger, a disability rights activist who was one of the first to place his wheelchair in front of a bus in the early 1980s. "Her genius was that she saw the bus as the great integrator: It took you to work, it took you to play, it took you to places that you had never before seen. We began to see the bus the same way, too, and it empowered a group of people who had been just as disenfranchised as African Americans."

The disability rights movement could in no sense have been called a movement when Parks refused to yield her seat. At that time, the unemployment rate for people with disabilities reached over 70 percent, and organizations that rallied for rights for people with disabilities focused on solutions that were specific to a single disorder. "The disability community was fragmented,"

says Bob Kafka, a quadriplegic who broke his neck in 1973 and who was an early organizer for ADAPT. "The deaf community wanted interpreters. People with mobility issues wanted curb cuts. The blind wanted more sensory communication. Everyone saw themselves as a deaf person, or a blind person, or a mental health person. We were tossed salad, not fondue."

Parks's action offered these separate communities a strategy that unified their various wishes. "Rosa Parks energized us in that she was the perfect symbol for when the meek become militant,"

says Kafka. "She was someone who was willing to cross the line."

And the fight for accessible public transportation was to be the single issue that catalyzed disparate disability groups into a common cause.

By the 1960s and '70s, many cities had introduced paratransit services that picked up disabled patients. The officials who controlled city budgets, though, typically stipulated that these buses could be used by an individual only a few times a month and that the buses could be used only by appointment. So, in the late '70s and early '80s, some activists began to extend the logic of Parks' silent act of defiance to their own cause: Buses that divided people into separate categories, they said, were inherently unequal. Disabled people shouldn't be limited to using paratransit buses. They deserved to ride the city buses, just like everyone else.

"How could you go to school, or go on a date, or volunteer somewhere if the only trips deemed worth funding for you were medical trips?"

wrote ADAPT member Stephanie Thomas in her introduction to To Ride the Public's Buses,

a collection of articles about the early bus actions that appeared in Disability Rag. "How could you get a job if you could only get 3 rides a week? If you were never on time?"

Parks's method of dissent -- sitting still -- was well suited to a community in which many people found themselves having to do that very thing all day long. Within two decades of her refusal to give up her seat, disabled people in cities across the country began staging their own "sit-ins"

by parking their wheelchairs in front of ill-equipped city buses -- or, alternatively, by ditching their wheelchairs and crawling onto the stairs of the bus vestibules.

Some of the sit-ins were individual acts of defiance. In Hartford, Connecticut, 63-year-old Edith Harris parked her wheelchair in front of 10 separate local buses on a single day after waiting nearly two hours for an accessible bus. Increasingly, though, the sit-ins were organized by ADAPT and involved many wheelchair users at a single location.

These actions began to change both how disabled people were perceived and how they perceived themselves. "Without the history of Parks and Martin Luther King, the only argument that the disability community had was the Jerry Lewis Principle,"

explains Auberger. "The Poor Pathetic Cripple Principle. But if you take a single disabled person and you show them that they can stop a bus, you've empowered that person. And you've made them feel they had rights."

The sit-ins also began to bring about concrete changes in the policies of urban transportation boards. In 1983, the city of Denver gave up its initial resistance and retrofitted all 250 of its buses with lifts after 45 wheelchair users blocked buses at the downtown intersection of Colfax Avenue and Broadway. Similar moves were made by Washington's Metro board in 1986 and by Chicago's transit authority in 1989. And in 1990, when the landmark Americans With Disabilities Act cleared Congress, the only provisions that went into effect immediately were those that mandated accessible public transportation.

If Rosa Parks left a lasting legacy on the disability rights movement, it is important to recognize that it is a legacy that is largely unfinished. A restored version of the bus that Rosa Parks rode in Montgomery recently went on display at the Henry Ford Museum near Detroit, the city where Parks lived her last decades and died last Monday. Detroit's mayor, Kwame Kilpatrick, who is up for reelection on November 8, memorialized Parks by saying that "she stood up by sitting down. I'm only standing here because of her."

Kilpatrick failed to mention a further irony, though: The Justice Department joined a suit against his city in March. It was initially filed in August 2004, by Richard Bernstein, a blind 31-year-old lawyer from the Detroit suburb of Farmington Hills, on behalf of four disabled inner-city clients. His plaintiffs said that they routinely waited three to four hours in severe cold for a bus with a working lift. Their complaint cited evidence that half of the lifts on the city's bus fleet were routinely broken. The complaint did not ask for compensation. It demanded only that the Motor City comply with the Americans With Disabilities Act. The city recently purchased more accessible buses, but the mayor didn't offer a plan for making sure the buses stayed in good working order. He has publicly disparaged Bernstein on radio as an example of "suburban guys coming into our community trying to raise up the concerns of people when this administration is going to the wall on this issue of disabled riders."

Mayor Kilpatrick is not going to the wall, and neither are many other mayors in this country. A 2002 federal Bureau of Transportation Statistics study found that 6 million Americans with disabilities still have trouble obtaining the transportation they need. Many civic leaders and officials at transit organizations have made arguments about the economic difficulty of installing lifts on buses and maintaining them. But they are seeing only one side of the argument: More people in the disability community would pursue jobs and pay more taxes if they could only trust that they could get to work and back safely.

Public officials who offered elaborate eulogies to Parks' memory last week should evaluate whether they are truly living up to the power of her ideas. During a visit to Detroit in August to speak to disabled transit riders for a project I was working on, I met Robert Harvey, who last winter hurled his wheelchair in front of a bus pulling onto Woodward Avenue after four drivers in a row had passed him by. (He was knocked to the curb.) I met Carolyn Reed, who has spina bifida and had lost a job because she could rarely find a bus that would get her to work on time. Her able-bodied friends had also recently stopped inviting her to the movies. She guessed why: A few times over the past months, they had found themselves waiting late at night with her for hours to catch a bus with a working lift. "I'd say, 'Go ahead, go ahead, I'll be all right,' "

she told me. "And they'd say, 'We're not leaving you out here.' "

I also met Willie Cochran, a double amputee who once waited six hours in freezing temperatures for a bus that would take him home from dialysis treatment.

None of this should be happening in America. "Rosa Parks could get on the bus to protest,"

says Roger McCarville, a veteran in Detroit who once chained himself to a bus. "We still can't get on the bus."

A true tribute to Parks would be to ensure that every American can.